Lucrecia Martel, without a doubt, is one of the most celebrated auteurs of our times. In a career spanning over two decades, she has successfully made a mark as a unique voice in the world of contemporary cinema, even though she has made only 4 feature-length films to date. Her 2001 debut La Ciénaga was enough to put her on the world map as someone who not only has great mastery over the craft but also as someone who can effortlessly forge a distinct cinematic world of her own. Her subsequent ventures The Holy Girl (2004) and The Headless Woman (2008) have only strengthened her place as an auteur. The layers at which a Lucrecia Martel film works are multiple and complex; hence, viewing or even trying to analyze her films through a single prism is futile. But one recurring and prominent aspect of her films is how she explores sexual tension between her characters and her extraordinary ability to build scenes around it.

There have been many masters in the history of cinema who have explored understated sexual tension between characters in various ways, but what makes Lucrecia Martel so unique is how she can make sexual energies an intrinsic part of her mise-en-scène through the use of lens, composition and movement of characters within the frame. More interestingly, many of her shots are usually static shots. How she shoots human bodies and how, at times, she makes body parts the most prominent element in the frame is also quite idiosyncratic to her style. Many a time, Martel goes for a very unconventional composition while framing human beings, especially when there is more than one. By doing so, she brings out the bodily proximity or physical warmth between characters more swiftly than what would have been the case had she gone for a classically conventional composition or even choice of lens. The very first sequence of La Ciénaga, where a few members of a bourgeois family relax by the poolside in silence, brings out this element of her shot-taking quite gracefully.

Martel’s central characters are usually from bourgeois families of European descent. Growing up in a bourgeois household in Salta herself, she has never shied away from expressing her disgust for the class she belongs to in her interviews, which is also quite evident in her films. She loves exploring and critiquing the perennial hollowness and self-indulgence existing in the lives of contemporary white bourgeois societies in various ways; and at times, exploring sexual frustrations and sexual exchanges between characters become a tool for her to enhance that. Her characters are complex and layered, to say the least. The most wonderful thing about her as a filmmaker is how she can peel off those layers gradually as the film progresses, teasing the viewer’s perception of the characters throughout. Her mastery always lies in how much she conceals from the viewer about the world of her characters rather than letting them into it through a direct path.

Veronica, the leading lady in The Headless Woman (2008), played by the magnificent Maria Onetto, hits something with her car by mistake, which she fears to be a human. With an extremely unsettled state of mind, but trying to maintain her poise at the same time, she goes to a hotel room at night instead of going home directly. There she meets Juan, who tries his best to understand what brought her to the hotel that late at night, simultaneously trying to calm an unnaturally unsettled Veronica. Martel doesn’t immediately give away what sort of a relationship these two might share, delaying the moment where they might have a one-on-one private conversation. Juan appears to be her husband at first. But by the nature of the conversation between them, it gets clearer slowly that he is not. When finally both of them get into the room and Veronica has a moment to speak about what had happened, she doesn’t. There is a strange calmness on her face as if she is not in any hurry to do or say anything. Instead of talking, a moment later, they start making out, which Veronica initiates when Juan says “I’m leaving”. Their passionate lovemaking ends with a mild giggle from Veronica. Her unusual behavior in a situation like this might take the viewers aback at first, but it doesn’t feel very out of place either, considering how Martel has built on the sexual tension between the two characters ever since they met in the film through looks and pauses, and not dialogues.

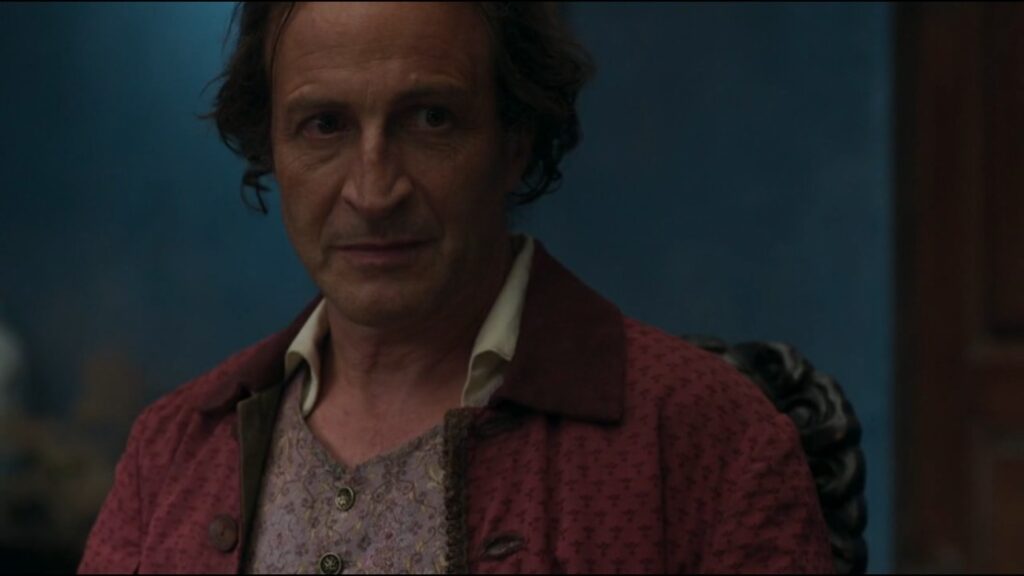

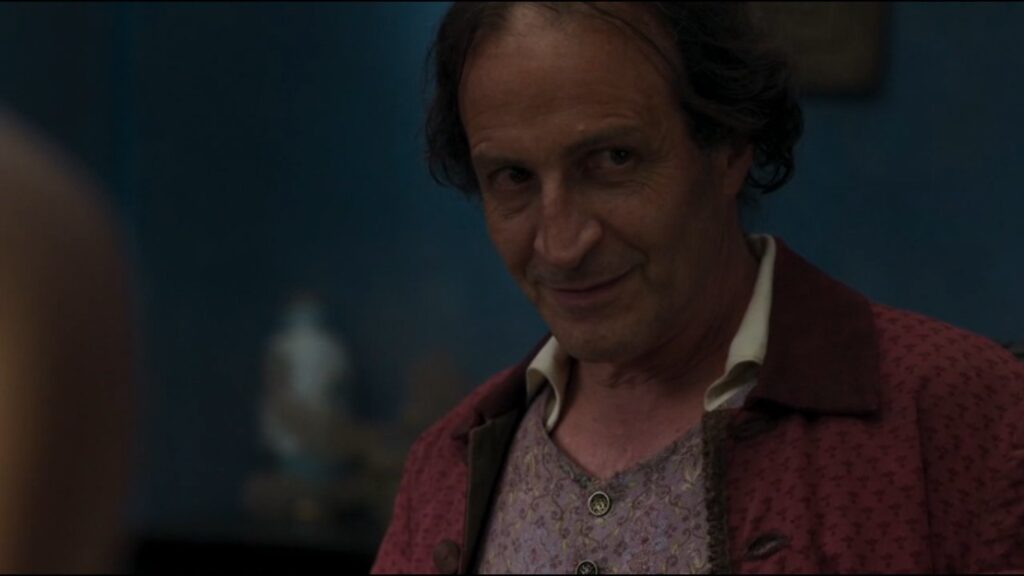

In the initial half of the scene, Martel delays any sort of intimate conversation between them by using interruptions by other people in the hotel. The stills above are from the first moments they get some time in private after closing the door of the room. None of them are speaking. Veronica is taking a moment to think something, before looking at Juan, who is standing by the window (Still 1). Martel immediately cuts to Juan, who is caught already looking at her (Still 2). But as soon as Veronica looks at him, Juan averts his gaze and looks outside and the silence prevails again for quite some time.

Later in the film, it is also seen that Juan is a friend of Veronica’s husband and is also familiar with her family. Even when these two characters meet later in the film at a family gathering (above still), they try to snatch away a moment for themselves, while continuing with the banal chat they were having. Martel doesn’t take, or rather, doesn’t need much screen time to tickle the romantic or sexual nature of their relationship in this scene- as if she is also trying to snatch away a moment like Veronica and Juan, to divert the viewer’s mind to them amid the chaos that is going on in her life. This nature of Martel’s characters is prominent in all her films, where the sexual dynamics the characters might share are not specified and are left vague deliberately.

One such fine example in another film of hers is the dynamic between Helena and Dr. Jano in The Holy Girl (2004). The film revolves around a teenage girl Amalia and her exploration of sexual awakening at that age, coupled with her deep passionate religious faith. But while taking the viewers on the journey with Amalia, Lucrecia Martel doesn’t fail to flesh out other characters to their fullest, especially Amalia’s single mother, Helena. The entire film takes place within a span of a few days when a medical conference is being held at a hotel; and that is where Helena (owner of the hotel) and Dr. Jano meet, who have come to participate in the conference. The very first meeting between these characters is at the poolside. Even though the scene doesn’t have any dialogue, Martel pulls out the trick of “looks” and “pauses” between the characters to form some sort of connection. In the next scene where the two characters meet, a conversation takes place in the bar. During the scene, Martel very cleverly evokes that both Helena and Dr. Jano are interested in one another at some level. A lot of people are around them constantly during the conference and the filmmaker very masterfully uses this chaos to amplify the feeling of sexual tension between the two characters- as if something definitely would have happened if they could find a moment of their own, even though Dr. Jano is a married man. She builds this tension through the first hour of the film so tactfully that when Helena and Dr. Jano are alone in a room for the first time in the film, there is constant teasing with the viewer’s expectations from Martel’s side. The scene runs for around 3 minutes and right from the beginning, Martel pumps up the sexual energy of the scene, not so much through dialogues, but mostly by using the gaze of one character for the other one. The sensuous nature of that “gaze” and how wonderfully she captures it to enhance the inherent energy of the scene is as good as filmmaking can get.

She starts the scene with a two-shot, making them sit in a slightly formal manner, maintaining a fair amount of distance.

But as the scene and their conversation progresses, Martel makes Helena go inside her bedroom and carry forward the conversation from there, as Dr. Jano waits in the living area. The distance between them helps in mounting up the sexual tension as Dr. Jano’s desire to follow Helena to the bedroom can be felt in his prolonged wait. On the other hand, Helena also seems like she wants to invite him inside, almost dropping hints for him from time to time through her looks, gestures, and even dialogues.

Finally, a few moments later, Helena calls him and he goes inside to have a look at Helena’s dress. The tension building up throughout the scene reaches its peak at that moment, almost like a volcano ready to erupt. Martel also brilliantly stretches this moment by not letting anything happen, but bringing them closer to each other several times. Dr. Jano leaves her room eventually and nothing materializes between them, but the final shot of the scene also doesn’t fail to capture the sexual tension in its truest sense- as if teasing the audience till the last moment, even after he opens the door to go outside.

Lucrecia Martel’s films contain this sort of exchange of sexual energies between the secondary characters as well (even between two female characters), no matter how little screen time they might have in the film. The daughter and the maid in La Ciénaga, Amalia’s friend and her cousin (or maybe, distant cousin) in The Holy Girl who appear together in the film for two or three scenes, Veronica and her niece in The Headless Woman are a few examples of it. In the larger scheme of things, these sub-tracks (or some side characters) might seem somewhat inconsequential, but it is difficult to refute the fact that they add a lot to the eventual arc of the film, or shape up the lead characters in most cases.

In Zama (2017), Lucrecia Martel’s latest period drama, the lead character Zama’s attempts at seducing Luciana, played by Lola Duenas, and the way the filmmaker shapes up their encounters at various junctures of the film is a great example of how one can play around with sexuality of human beings. Martel skillfully taps into different shades of sexuality in this film and how, many a time, one’s sexuality can be used in many other layered ways. In a brilliant scene from the film, Zama goes to Luciana’s house at an odd hour, only to find out that she is inside the bedroom with his colleague, Prieto. Martel doesn’t specify the reason why Zama knocks on her door at such an hour, but the previous meeting between them is indicative enough. In that scene, Luciana asks Zama for help regarding her maid’s marriage and leaves no stone unturned to charm Zama with her seductive gestures. She even ends the conversation with Zama by saying “You deserve a kiss”, after evading an attempt from him to kiss her. But as Zama waits eagerly for her to take things forward, she says “Not now” instead. Zama stands still, looking helpless, pondering over how close he had been to a sexual encounter he desired for a long time. Martel artfully adds another layer to it by using Zama’s sexual jealousy as the main catalyst to heighten the enmity in the already strained relationship Zama shares with his younger colleague – as if “sexual triumph” stands as a sign of victory in this regard.

In the very first meeting between Zama and Luciana, this play of making and avoiding eye contact between them becomes very crucial in carving out the dynamics they are going to share in the course of the film. Martel makes things more layered as she usually does, by using other people present in the room. While another person is having a conversation with Luciana, Martel mostly stays with Zama (in a medium close-up) looking in awe at her and doesn’t cut to the person speaking. A moment later, while talking about theatre troupes in Buenos Aires with the third person, she says “We don’t have any occasion for elegance here.” Zama quickly barges in to shower a compliment on her, as if it came out of his mouth as a reflex action- “That’s not something you lack.” Till that moment, Martel keeps Zama mostly silent and focuses more on his gaze towards Luciana. It is this very nature of her editing pattern that adds to the kind of undertone of the sexual energy flowing through the scene effortlessly.

Both the stills above are part of the aforementioned scene, seen at different parts of the conversation. In the latter half of the scene, when the third person leaves and Zama is also about to, Luciana calls him to sit by her side. This time, they have a more intimate conversation and Martel tactfully frames them with a different lens and in a way that heightens the buildup of Zama’s attraction towards the lady. Even the way she composes the two shots she uses when Zama sits on the sofa for the first time is quite unconventional.

She uses similar kind of lensing and compositions in her other films as well.

Interestingly, both these scenes are very similar, not only in terms of what they try to explore and the way it unfolds but also the fact that these scenes appear almost at a similar point in the respective films in relation to the graph of the dynamics between the characters in question.

In both the scenes shown in the stills, Martel gives a very banal activity to the characters. But as the scene progresses, she diverts the attention of the viewers very cleverly from the activity to the sexual tension that can be felt in the air. In the scene from La Ciénaga (Still 2), the girl is taking a bath and her cousin barges in to clean his shoes and feet. While using the shower to do so, he spends quite some time there, making eye contact with her many times. Both of them keep giggling throughout but do not exchange any lines apart from the girl asking him to “get out” twice. But Martel also makes sure to convey to the viewer that the girl doesn’t mean it, as the filmmaker elongates the moment to give enough time for the sexual energy to mount up. It’s also interesting how she starts the scene. When the guy entered the bathroom, he was initially cleaning himself in the basin, not entering the area where his cousin was having a shower. But slowly when he moves to that area, Martel decides to cut to the feet of the characters first rather than cutting to their faces. So, it’s the naked feet of two people we see in the frame first, and then their respective faces together.

Another recurrent trick she uses in her films is how she frames the first meeting (in the film) between two characters and she is quite aware of the mark it would leave on the viewers. Many times she would construct the first scene between two characters in such a way where physical touch, of any sort, is a major part of the scene. She does this quite often in different parts of her films- giving an activity to the characters with some sort of bodily touch involved in it; such as putting lotion or powder on the chest, massaging one’s hair with oil, putting water over the back side of someone’s neck (still below) etc.

Both the stills (Still 1 & Still 2) are from the first scene between the two characters in the respective films. In fact, in the case of Still 2, this is the very first shot between Veronica and her niece in The Headless Woman. Even though Martel doesn’t give too much screen time for these two characters together in the film, during 2-3 scenes, she brings out the niece’s sexual affection (running on the thin edge of desperation at times) for her aunt quite cheekily. She even tells her aunt at one point in a subtly frustrated manner – “Love letters are there to be responded to”, which comes slightly after she tries to lean towards her aunt for a kiss. And right from this very first shot between these characters, Martel successfully injects this thread into the viewer’s mind, without them even realizing it. But it’s not only about how she composes her characters and uses their body parts; it is also about how long she stays with a shot to prolong that feeling of sexual tension. Often, the scenes have no or minimal dialogues; and that’s when Martel’s mastery to enhance this feeling through silence takes the front seat.

Another peculiar feature in Lucrecia Martel’s films is how she makes her characters move within the space to increase or decrease the relative distance between them and uses these movements pretty effectively to intensify the sexual tension. In a scene from La Ciénaga, the teenage girl, after having a conversation with the maid, enters the room. Her cousin and his mother are sleeping on the bed. When she enters the room, her cousin notices.

She continues using the mirror to put lotion on her body, and Martel uses that broken structure of the same mirror to compose both of them in the same frame. They keep exchanging looks with each other throughout. He even carefully whispers something to her, trying his best not to disturb his mother.

After a while when she is done, she goes near the bed suddenly and plays a prank on him by pulling him slightly out of bed to go outside. The mother wakes up with a jolt and the cousin follows her. She takes a dip in the swimming pool by the time he reaches outside. There are other people (mostly kids) in the family by the poolside, as they spend some time together. The beauty of the scene lies in how masterfully she keeps playing with the distance between the two characters and the look exchanges between them through day-to-day normal activities. This scene adds a lot to the sexual energy these two characters share, which she elevates by multifold in some of the latter scenes in the film.

One of the often overlooked aspects of Lucrecia Martel’s films is the intricate sound design and her use of distinct elements in the soundscape to amalgamate with the Mise-en-scène. The design in the opening sequence of La Cienaga is something that stays with the viewers for a long time, where she uses prominent sounds of glass, bottles, chairs, etc. to almost create some sort of a background score – a symphony of its own. The sound of the hand fan in the first meeting between Zama and Luciana in Zama, the sound of the electric tube and the distant car siren in the hotel room scene in The Headless Woman, and the sound of a musical instrument playing in the lobby in the conversation scene between Helena and Dr. Jano while eating at the restaurant are some of the best examples of how Martel chooses specific elements to lead the race in her overall sound design.

Lucrecia Martel is, in a way, the flag bearer of the New Argentine Cinema, a movement that came to prominence at the turn of the century as sort of a reaction to decades of political and economic crisis in the country. She is single-handedly responsible for attracting the movie-going world’s attention to contemporary Argentine cinema and Latin American cinema at large, even outside the festival circuit. The “Queen of Transnational Auteurism”, as deemed by many, has made films (at least the first three) revolving around similar themes, characters and backdrop all her life. But she has successfully evaded the risk of being repetitive or self-indulgent, a quality she hates about her own socio-economic class.

Source link