Credit: National Institutes of Health

The US molecular biologist Maxine Singer made discoveries about the role of enzymes in assembling genetic material. Work in the same field led to the first experiments in genetic engineering (or recombinant DNA) — a topic that sparked debate among scientists and the public alike. She fully engaged with these concerns and became a key advocate for dialogue between scientists and society. In later life, as an influential scientific administrator, she championed the cause of marginalized people in science and founded innovative programmes to support science teaching in schools. She has died aged 93.

In 1972, Paul Berg, who would go on to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, successfully inserted DNA from a monkey virus into the genome of the bacterium Escherichia coli, in the first such genetic-recombination experiment. In 1974, Berg and others sent a letter to several journals, including Nature, calling for a voluntary moratorium on recombinant-DNA research — to quell fears of genetically modified organisms escaping and spreading disease — and a scientific conference to address potential hazards. Singer co-organized the 1975 conference at Asilomar, California, at which scientists, lawyers and other interested parties thrashed out a way forward, and she co-authored its report (see Nature 255, 442–444; 1975).

It’s time to admit that genes are not the blueprint for life

At the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), Singer helped to draw up guidelines on the safety and use of genetically modified organisms in the laboratory. She helped to head off attempts to ban recombinant-DNA research, giving media interviews and testifying to the US Congress. She and a colleague, co-wrote the guidelines’ environmental-impact statement, judging that it would be quicker and less expensive to write it themselves than to teach molecular biology to environmental consultants. “I think we succeeded in what we were trying to do,” she later said, “which was to demystify things and have reasonable regulations but not legislation”.

Born Maxine Frank in New York City, Singer grew up in Brooklyn and attended local public schools, where a teacher encouraged her love of chemistry. She went to Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, for a PhD in protein chemistry. It was there that she first learnt of exciting developments in nucleic acids — including work by geneticist James Watson, biophysicist Francis Crick and chemist Rosalind Franklin on the double helical structure of DNA.

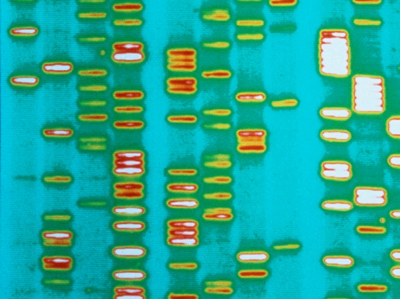

In 1956, she moved to the biochemistry lab at what is now the US National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases in Bethesda, Maryland. There, she explored the role of enzymes in forming artificial nucleic acid polymers (such as UUU). These studies contributed to the work of geneticist Marshall Nirenberg and others that cracked the genetic code by working out how the sequence of bases in nucleic acids corresponded to the sequence of amino acids in a protein.

She found the research environment at the NIH welcoming and, unlike colleagues at universities, initially experienced little prejudice on the grounds of her gender. She recalled that, between 1959 and 1964, she was “essentially pregnant all the time” (she had four children), but no one objected. It was only when she had her own independent group at the NIH that she realized that postdoctoral researchers, of all genders, were reluctant to work for a woman. After that, Singer did all she could to reduce the numerous barriers facing women in scientific careers.

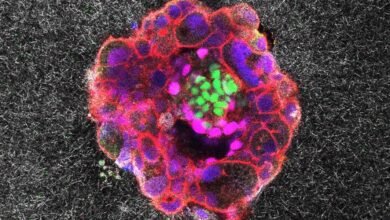

In 1971, she went on a year’s sabbatical to the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, to learn about monkey tumour viruses and animal cell culture, having previously worked with bacterial nucleic acids. She began using restriction endonuclease enzymes to incorporate viruses into animal genomes, which put her at the centre of the debate on recombinant DNA. Her informed perspective, combined with her commitment to science as a public good, made her a trusted negotiator, and she was not afraid to cross swords publicly with powerful figures such as Watson, who called for an end to the moratorium within six months of having voted for its introduction.

Guidelines on lab-grown embryo models are strong enough to meet ethical standards — and will build trust in science

In 1975, she moved to the US National Cancer Institute (NCI) in Bethesda, setting up its first nucleic-acid biochemistry section and later heading its biochemistry lab. There, she discovered that LINE-1, a group of DNA sequences, is a transposon, or jumping gene, that can move around the chromosome and cause mutations.

Frustrated with increasing levels of bureaucracy at the NIH, in 1988 she became president of what is now Carnegie Science in Washington DC, keeping her NCI lab going for the first ten years of her term. She threw herself into initiatives to improve resources for pupils and science teachers in public schools, bring science to the public through lectures and hands-on activities and promote the participation of marginalized groups, including women of any ethnicity, in science. She also steered through the construction of telescopes at Carnegie’s astrophysics observatory at Las Campanas in Chile, and established a research department in global ecology.

Singer retired from Carnegie in 2002, but continued to work on outreach programmes in Washington DC. In 2003, with Paul Berg, she co-authored a biography of the geneticist George Beadle, who discovered the connection between genes and proteins. Among many other honours, she received the National Medal of Science from then-US president George H. W. Bush in 1992.

“Science is not an inhuman or superhuman activity,” Singer told the journalist Bill Moyers on a television programme in 1998. “It’s something that humans invented, and it speaks to one of our great needs — to understand the world around us.”

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Source link