Black lung is a cruel disease. Incurable, it scars and hardens lungs, makes breathing hurt and leads to tuberculosis, heart disease and cancer. Still a recurring threat to miners, it is preventable by controlling exposure to dust in mines. We know that thanks to federal scientists the Trump administration now aims to wipe out. That’s a mistake that threatens everyone.

In March, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., restructured away some 20,000 agency workers, ones who do everything from checking food to investigating HIV outbreaks. Among them in April were 873 of the roughly 1,300 people employed by the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, the $363 million agency which ensures the trustworthiness of firefighter respirators, surgical gear and construction-site safety monitors and oversees most every other aspect of workplace safety.

The decision to fire NIOSH scientists—alongside such genius moves as cutting the lead poisoning prevention office at CDC and forcing the resignation of the FDA’s trusted chief vaccine safety official—point to a fundamental blind spot of the Trump administration: People won’t work in mines or fight fires or drive cars or take new drugs, it turns out, if they don’t believe they’re safe. And they won’t be safe in Trump’s “golden age” economy, because the scientists testing their workplaces and equipment are missing.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

NIOSH is best known, to the extent that it is known at all, as the institute that rated mask performance in the COVID pandemic. But some 50 million U.S. workers wear some type of respirator on the job, says Cam Mackey, president of the International Safety Equipment Association, all tested and certified by NIOSH.

“A lot of people have never heard of this agency and therefore might assume that it doesn’t do anything valuable. But in fact, the opposite’s true,” says Mackey. “It does absolutely groundbreaking work that no one else does and probably no one other institution would do. The sad reality is without NIOSH, workers are going to get sick. And workers are going to die.”

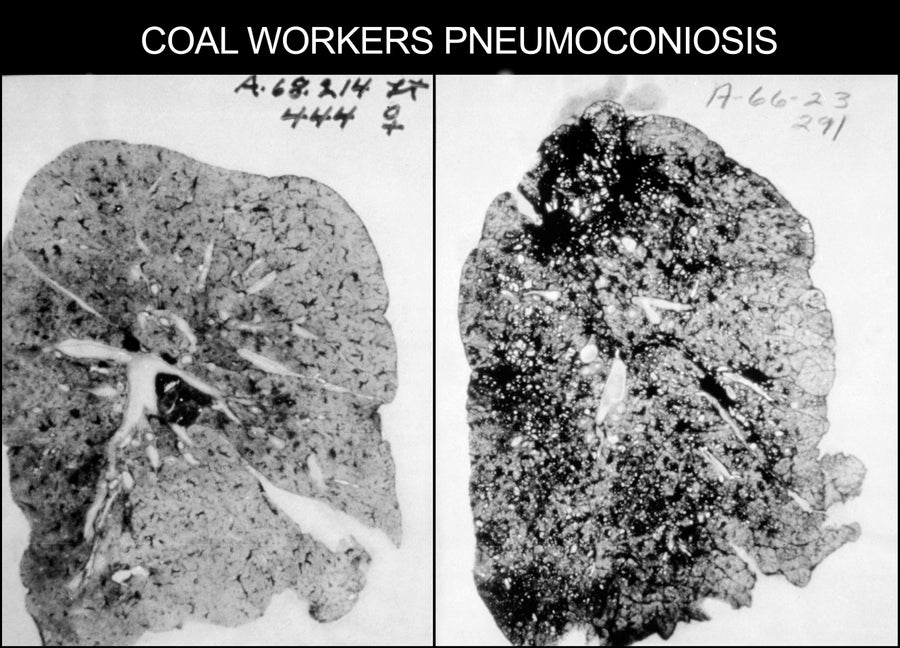

An occupational health image from 1973 shows the lungs of a coal worker with Pneumoconiosis, or Black Lung Disease.

Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images

Some 210 of the NIOSH job cuts landed at its Morgantown, W. Va., lab, which began in 1967 as the Appalachian Laboratory for Occupational Respiratory Disease, studying black lung disease just as coalfield demands for treatment there spurred a protest movement. The lab runs free black lung screenings for miners, which are mandated by a 1969 law but now appear in jeopardy.

One of the Morgantown scientists who lost her job is Catherine Blackwell, who was put on administrative leave from her research position. She studies what happens to people’s immune systems when they encounter mold and other contaminants in buildings, cannabis or hemp dust in grow facilities, wildfire smoke that firefighters breath in, and coal dust.

She tells Scientific American that her entire branch was shut down. As a young researcher, she chose government science because the work she would do would benefit everyone.

“Workers are going to be immediately less safe,” she says, if no one is testing masks and respirators.

Elsewhere, the institute runs a firefighter fatality investigation program, which investigates deaths and issues safety recommendations. It funded a study looking at cancer rates among firefighters that led to changes in safety protocols around smoke, fumes and soot. Those now save firefighters about $71 million per year in medical costs and lost work, and more importantly, they save 15 to 45 lives per year, according to a 2017 RAND study. The economic benefits of just six NIOSH programs alone, including the firefighter cancer study, exceed the institute’s entire research budget, noted a 2023 American Journal of Industrial Medicine report.

Another NIOSH case study looked at rules limiting concrete dust from asphalt milling machines on roads, which is linked to lung cancer. They saved hundreds of lives, with an economic benefit ranging from $304 million to $1.1 billion a year. Highway construction work is already famously dangerous; adding any cancer risks to workers building overpasses and roads is just cruel.

Without NIOSH, private industry simply will not pick up its work ensuring safety equipment is safe. We know this from the pandemic, when NIOSH tested imported N95 and KN95 masks that were suddenly appearing on the market in 2020 and found around 60 percent failed tests. “Businesses have to make money, and this kind of research costs money,” Markey says. “That’s what the government is for, to do this kind of research.”

The pandemic also taught us deeper lessons about safety and trust that Trump and his allies are serially botching, and not just with the NIOSH lay-offs. RFK, Jr., a “proven menace to public health,” as health journalist Maggie Fox wrote in November in Scientific American, is again putting lives at risk by downplaying the Texas measles outbreak, notwithstanding a recent post endorsing the MMR vaccine. By removing Peter Marks, the FDA vaccine official who worked hardest to ensure scientific confidence in Operation Warp Speed’s hurriedly developed vaccines, Kennedy has set us up for even wider vaccine hesitancy in the next pandemic. For an example, consider the poor pandemic performance of Vladimir Putin’s Russia, the government Trump seems to most wants to emulate. Despite Russia releasing the first COVID vaccine in 2020, only 19 percent of the population was vaccinated a year later. That’s because nobody trusts a vaccine pushed on them by an authoritarian serial liar. It’s something for Trump to bear in mind.

RFK, Jr., has suggested that around 20 percent of fired HHS workers would get their jobs back, “because we’ll make mistakes.” That’s either an open admission of incompetence or, as reported by Politico, dishonesty. Regardless, he plans to fold a denuded NIOSH into a smaller Administration for a Healthy America, with workplace safety not among its listed priorities. Why anyone wants this guy to run a lemonade stand, much less a $1.8 trillion federal agency, remains a mystery.

What nobody wants is to rush into a burning building wearing a respirator they don’t trust, says Mackey, the safety equipment official. “Our promise to workers is that we’ll give you a fair living wage and make sure that you can go home safe to your loved ones at the end of the day. And, and that’s the challenge here. The workers are the ones that are losing out.”

FPG/Archive Photos/Getty Images

Ultimately, some 125 million U.S. workers use personal protective gear on the job, from nurses to construction workers to paint sprayers. And because of cuts to NIOSH, Mackey added, “they’re going to be at risk and that’s going to keep people away from manufacturing jobs, that’s going to make manufacturing jobs more dangerous.”

Due to more accidents and illness, medical costs will go up, along with workers’ compensation costs, which will decrease productivity. Businesses that focus on best safety practices save money. And safety rules, for everything from making drugs to building roads, are what have allowed industries, from pharmaceuticals to construction, to grow so large in the first place. People like their medicines, and their jobs, to be safe.

Little considered until they’re gone, agencies like NIOSH are the glue holding the economy together. From the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, which led to the FDA, to the Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969, passed under pressure from the black lung movement, the laws that created the health agencies now facing severe cuts or outright elimination were meant to allow just the kind of manufacturing economy that Trump says he wants to flourish.

“That’s the risk here,” says Mackey. This will really kind of put a damper on any type of manufacturing renaissance.”

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.

Source link