There’s a sliver of Prospect Park captured by photographer Jamel Shabazz that’s transported from another dimension, hidden away from the mess and noise of Parkside Avenue and the endless cycle of runners and bikers haunting the Park Drive loop. Embedded in a legion of trees, hidden from the rest of the world, is the 60-acre lake that winds through the bottom half of the park. Save for the emerald intrusion of Duck Island, there are times when the lake seems like it’s the end of the universe, blending into the horizon. On my bike rides, I’ll let the path carry me to the shoreline of the lake and stumble across the exact locales from one of Shabazz’s images. One witnesses a local fishing on the banks, or couples nestling into each other on a bench overlooking the lake, stationed for what feels like an eternity. It’s as though we’re all drawn to that freshwater magnet.

Jamel Shabazz © Michael McCoy, 2016

That sensation, the pursuit of pure tranquility, is at the core of Shabazz’s latest book, Prospect Park: Photographs of a Brooklyn Oasis, 1980-2025. This latest collection from the veteran photographer, who made his bones capturing portraits of New Yorkers on the street since the mid-1970s, was cobbled together during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, when Shabazz embarked upon his normal archival process, which made for a painstaking, laborious act. “I went through thousands of photographs—it was the actual prints that I have thousands of. I went through thousands of negatives; I went through slides. So it was a very extensive process, which I totally enjoyed because it allowed me to time-travel back and revisit places and memories that I have through these photographs,” Shabazz says. “One of the things that my father taught me—he was a professional photographer—he stressed the importance of themes…I started to break all of the work into themes, and I put them in archival boxes. So I had Prospect Park, I had Central Park, I had my Subway Series, I had my ‘Father and Son’ series. It was just a matter of just archiving or organizing the work for future exhibitions.”

Though crafting a book solely focused on Prospect Park wasn’t always a part of Shabazz’s grand plan (“I never really saw any book opportunities come in, in terms of a solo book project on Prospect Park”), Shabazz has been laden with honors to this point. He received the Gordon Parks Foundation/Steidl book prize for his 2022 work Albums, which utilized previously unreleased images he’d collected through his street photography ventures between the 1970s and 1990s. He pulled off exhibitions of his portraits at places like the Brooklyn Museum, the Bronx Museum, and a current slate at Hofstra University called “Love is the Message.” And, in 2013, he was the subject of a documentary by the legendary Wild Style director Charlie Ahearn. But despite the abrupt change in scope towards a new 175-page collection rife with tender portraits, verdant landscapes, and loving candids that spans nearly five decades within the 585-acre realm of Prospect Park, the allure of this undertaking was always present.

Shabazz isn’t shy about evangelizing the park’s restorative powers, resting in its trees and lush greeneries that roll endlessly into the ether. For the acclaimed photographer, and the hundreds of others who meander in and out of his portraits, the park is a temple. “It’s a part of the healing process. For me, too, I gotta go there to just get close to nature. I reflect on the day’s events, the week’s events, the month’s events. I revisit my goals and objectives,” Shabazz says. “So, I look at the park as a place of refuge. That’s why I even called it an oasis, because it’s a place where I can go and really be at peace with myself. And I would always leave a better person because the streets are really hard, and it’s a lot of negativity out there, and I needed to escape that, periodically, just to get my balance back in my sanity, and be around people that were pretty much in search of the same thing.”

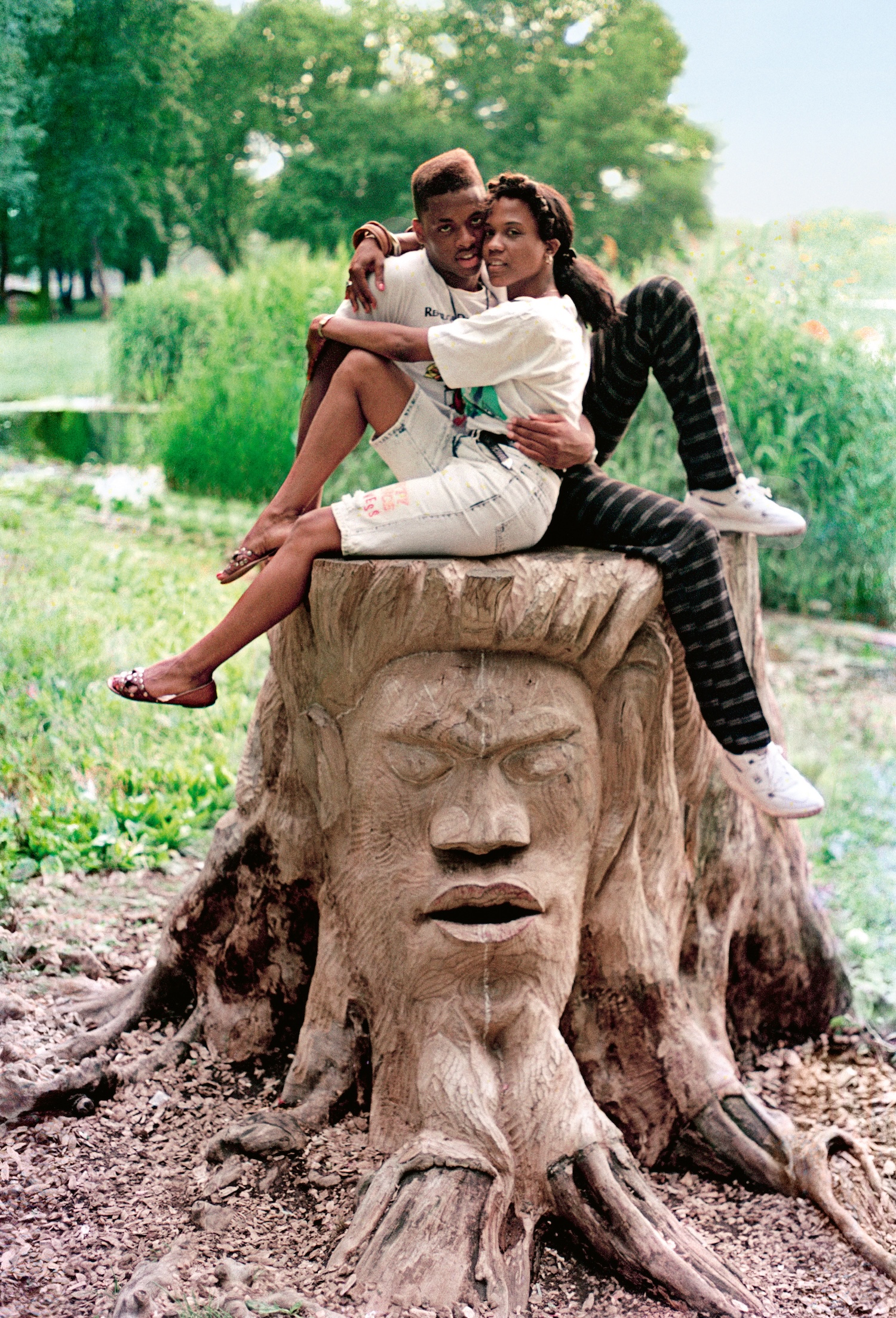

Prospect Park 1995 © Jamel Shabazz 2025

A project focused on Prospect Park feels almost predestined for Shabazz. The 65-year-old Brooklyn-born photographer grew up in the Red Hook projects in the 1960s and 70s, a stone’s throw from Gowanus Bay. His father, a professional photographer by trade, made their apartment fertile ground, nourishing a creative and curious child, stoking an interest in the arts. “We had an aquarium. [There] was always artwork on the wall. He had a really massive book collection that I would read all the time. He always bought home photography books. He took great pride in developing the family photo albums. Through his photographs from the Navy, I had an opportunity to see his traveling. So he created a love for photography for me before I even picked up the camera. It was all in the household,” Shabazz shares fondly. “He created a really beautiful environment for my family.”

It took Shabazz a little longer to take photography seriously for himself. Sure, he plodded around in junior high and high school with his mother’s low-frills Kodak Instamatic, taking portraits on a point-and-shoot film camera with reckless abandon—but at the time, it was just a hobby without any tangible steps forward.

He finally found himself with some free time in 1980 upon being honorably discharged from the army, following a 36-month tour stationed in West Germany. To rectify this, Shabazz, who was living in East Flatbush, began running four times a week at 5 a.m. to maintain his fitness and give his feet something to do—a symptom of the regimented sensibilities he’d contracted in the military. And with Prospect Park resting just a mile to his west, its expanse became a natural destination. He was also able to upgrade his equipment during this period, acquiring a Canon AE-1 camera with a 50mm, f/1.8 lens and a photo enlarger from a friend.

The upgrade caused Jamel’s father to take an interest in his son’s love for photography—a connection that was lacking before he had left for Europe. “That really bonded our relationship, because now he converted our laundry room into a dark room, and he taught me how to develop,” Shabazz says.

Prospect Park, 1982 © Jamel Shabazz, 2025

Jamel’s father gifted him an extensive collection of Time Magazine’s “Life Library of Photography,” which Shabazz subsequently pored over for hours and hours. When he would return home with a new roll of film and present it to his father, the elder Shabazz would pull out a red grease pencil and make corrections on the photos to show where they could be improved. During his time in the Navy, his father chronicled daily life on the USS Intrepid and worked as an aerial surveillance photographer. After returning home, he turned the apartment into a portrait studio, where he would photograph their neighbors. By Jamel’s own account, he was a hard teacher, but served as a necessary guiding hand.

Armed with a greater understanding of how to approach his new passion—tips like carrying your camera every day, mastering light conditions through repetition, and never having your cap on the lens—he brought his camera into the park on his runs. The escapes to the park were also perpetuated by Shabazz’s new job in the city’s Corrections Department. At 23 years old, he began working in the Adolescent Reception and Detention Center, specifically stationed to deal with pretrial detainees, which served as a front-row seat to the effects of the so-called “War on Drugs” on indiscriminately punished Black and Brown youths in the mid-80s. Each day, as he noted in Prospect Park’s introductory essay, presented new horrors. Apart from his family, Shabazz had only one place to turn to escape the brutal memories and sensations from his 16-hour days at Rikers Island. “I did a lot of running back then, so I would run in the park, kind of like come down off it,” he says. “A lot of times, I would get off work, I would have to go, even if I worked a double shift. I would have to go to the park, even just to smell the fresh air and the vegetation. Because inside the jail, the jail smells like dead rodents, sour milk, and cigarette smoke,” he recalls. “I really needed it to help me see the best of humanity…I needed to see hope. I needed to see love again. I needed to be reminded that there’s still good people around.”

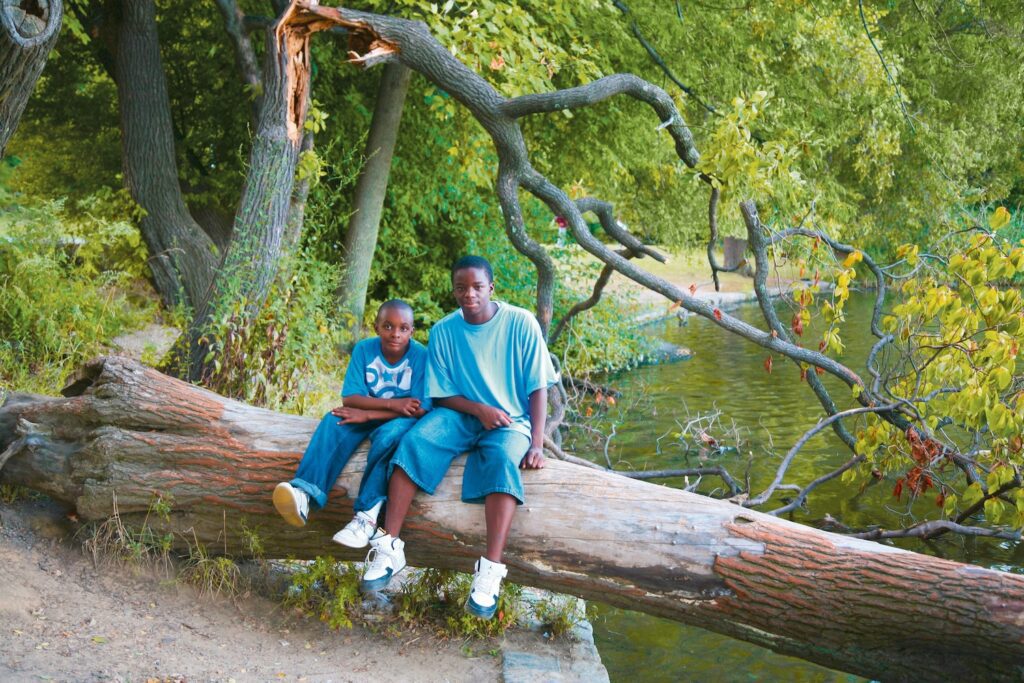

Prospect Park, 2000 © Jamel Shabazz, 2025

Prospect Park, a living, breathing 175-page document of his artistry and idiosyncrasies as a photographer, arrives as the centerpiece to Shabazz’s journey. Save for three interlude essays from Laylah Amatullah Barrayn, Richard E. Green, and Noelle Théard, who dive into their own relationships to the park —and their connection to the photographer—the endless run of portraits acts as a form of introspection for the 65-year-old.

Prospect Park, 1988 © Jamel Shabazz, 2025

Front and center are the shots of families and couples. Despite letting the camera be his compass on most ventures, he would enter the park with specific themes in his mind, hoping to catch a glimpse of whatever matched the underlying objective. Over that 45-year stretch, Shabazz strided right up to groups of people he’d see in the perfect spot for a shot, offering them two things: A compliment and a picture. “Love is a cornerstone of my work. So, whenever I saw love, whether they be children, parents with their children, couples in love with each other—that was always something that I focused on,” he explains. “I take time to talk to people before I take the photograph, you know. I want them to know what my intentions are. I want them to know that, ‘I see that you two really love each other, and that this picture is going to mean a lot.’”

As opposed to how he approaches his street photography—rearranging subjects to get the correct lighting and composition—these park photos occurred exactly how Shabazz found them on his walks. For him, the subjects have settled into their own spot in the park’s grand puzzle, and he was just lucky to have come across them at the perfect time. “Practically every photograph in that book is where people are where I met them, and I said, ‘Don’t even move. You’re fine, right where you’re at,’” he says. “The way you see people placed, that’s their special place. For many people, it’s a routine for them. ‘This is the way I sit, this is the way I go, this is my special place where I find inner peace.’”

And in dealing with artifacts of other people’s love, a practice that Shabazz takes as seriously as a cold, he applied the same level of care to the layout of Prospect Park. Even with the collaborative push and pull with publishing house Prestel Verlag, “a challenge” Shabazz welcomed, there’s a clear sense that the slate of “sister images” lined up next to each other, surrounded by vast white space and full page spreads that stretch tree trunks off the paper, are part of a meticulously planned narrative structure. With no captions underneath the photos, besides small text that denotes the year an image was shot, your eyes and mind are just left to connect the dots and realize how Black life in Prospect Park has evolved, or remained serenely steadfast, over the past 45 years.

Prospect Park, 2014 © Jamel Shabazz, 2025

Shabazz looks around at the concerted effort to stamp out hope and erase history on a societal and individual scale, and hopes that Prospect Park can arrive as a necessary salve for at least one reader’s soul. His photos aren’t the solution to the world’s problems, but to him, and to many others, they are proof of love existing, if just for a fleeting moment. “In essence…It’s almost like my work is medicine during the time that we live in. People really appreciate seeing images that reflect harmony and love and joy,” he says. “So I feel that I’m just living in accordance with my assignment right now, being a contributor, as I like to say, in preserving history and culture.”

“There’s a series of photographs that I made a point of having in my book, of people that have passed away. And their children have written to me and told me how much joy they feel in seeing their father in the book, the fact that I was able to preserve his legacy and capture him in such a dignified way. It is my hope that with my work that people could look at the images and be reminded of hope, because again, my work serves as a counter-narrative. For me, to present that counter in a time when a lot of negative images are being pushed out there, I have a responsibility as an artist to show the other side.”

Even as we meet at his “Love is the Message” exhibit in Hempstead, NY, a 75-minute trip on the LIRR from the boundaries of Prospect Park and his home for the past three decades, surrounded by his life’s work in a different realm, Shabazz is keenly aware of the pull of his idyllic land in the western hemisphere of Brooklyn.

“It’s a quiet place away from the concrete jungle,” Shabazz says, with his body pointed back in the direction of the park in the distance. “When you look at Flatbush Avenue, it’s a busy conduit: a lot of noise, a lot of pollution, a lot of activity. I love the wildlife that exists there. It’s always a joy to sit by the lake and just meditate. To me, it’s a sanctuary. It’s just an escape from the concrete, and it’s a place where I’m able to really connect with people on a real level.”

The post Jamel Shabazz’s ‘Prospect Park’ and The Pursuit of Pure Tranquility appeared first on BKMAG.

Source link