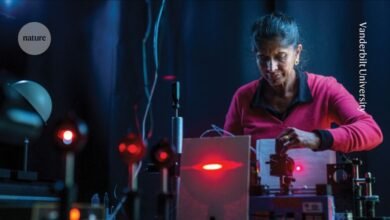

Despite having a strong healthcare system, vaccine hesitancy and mixed messages from government have curtailed some immunization efforts.Credit: Carl Court/Getty

When US officials announced earlier this month that they were shrinking the country’s roster of recommended childhood immunizations, physicians and scientists alike wondered what to expect. How much would infectious disease rates rise? Who would be most affected?

Half a world away, specialists in Japan say they have some hard-won wisdom to offer. They watched flu and pneumonia deaths spike after the Japanese government stopped pushing parents to have their children vaccinated against influenza. They witnessed rubella outbreaks driven by shifting vaccine guidance that left a segment of the population vulnerable. And they saw an unfounded media scare turn the public away from immunizations against human papillomavirus (HPV), which is responsible for nearly all cases of cervical cancer.

From that perspective, the US decision to pull back from vaccines is bewildering, several researchers told Nature. “It was shocking,” says Akihiko Saitoh, a paediatrician at Niigata University Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences in Japan. “The US had been leading immunization policy around the world. Now, it’s a completely different story.”

Changing schedules

The new US childhood vaccine roster, announced on 5 January, no longer recommends that all children should receive vaccines against rotavirus, COVID-19, influenza, meningococcal disease, hepatitis A and hepatitis B. That does not mean the vaccines will be out of reach: several remain recommended for certain high-risk groups, and all of the vaccines will still be covered by federal health-insurance programmes. Parents can still make their own decisions about whether their children receive the vaccines, at least for now.

How to speak to a vaccine sceptic: research reveals what works

Even so, the abrupt shift in guidance and rhetoric from the US government could affect vaccination rates by fueling vaccine hesitancy, which was already rising in some pockets of the country. And the absence of government backing for vaccines could create a legal risk for physicians who provide them, ultimately discouraging paediatricians from offering or encouraging immunization.

“There’s uncertainty about what might happen,” says Lauren Meyers, a computational epidemiologist at the University of Texas at Austin, “both in terms of how it will impact people’s behaviour, and what public-health and health-care impacts it will have.”

But some researchers in Japan say there are a few broad lessons to be learnt from their country’s troubled history with vaccines. Although Japan is a wealthy country with a strong health-care system, it has experienced several cases in which vaccine hesitancy and reduced government recommendations led to a decline in immunizations. In some cases, this was then followed by a scramble to catch up on missed vaccines when recommendations were reinstated.

Of the US changes, removing the recommendation that all children receive the flu vaccine is particularly surprising in light of Japan’s experience, says Hiroshi Nishiura, an infectious-disease epidemiologist at Kyoto University in Japan. For decades, it had been mandatory for Japanese schoolchildren to receive flu vaccines. But by the 1990s, vaccine hesitancy was rising and there were public doubts about the flu vaccine’s effectiveness in children. This, plus lawsuits against the government, led officials to discontinue their flu vaccine policy in 1994. Vaccination rates plummeted, says Nishiura. “Influenza transmission became extensive among schoolchildren.”

Deaths due to influenza and pneumonia, which is often caused by influenza, rose, especially among the elderly1. “Now, what is very shocking to me is that the United States is following that type of path,” Nishiura says.

Playing catch-up

The damage from removing vaccine recommendations in the United States could linger for a long time even if guidelines are reinstated. When vaccination against rubella, also called German measles, was first rolled out in Japan, it was only recommended for girls. The goal was to prevent congenital rubella syndrome, which can cause intellectual disabilities and heart defects in children born to mothers with the infection.

Source link